NUCLEAR POWER PLANT

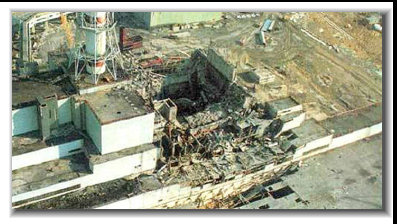

In 1986 a catastrophic reactor core meltdown occurred at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. The level 7 incident occurred during

a test that simulated an electrical power outage which deprived power to the cooling water circulation system. Massive amounts

of radioactive contamination were released. The contamination spread over parts of Russia and Europe and it is estimated that

the eventual death toll could be as much as 16,000 people. It is still illegal to live in the area near the power plant and radiation

levels in the control room are still fatal with a one-minute exposure.

Another level 7 meltdown occurred in 2011 when a massive earthquake and tsunami struck Japan. The reactors at the Fukushima

Daiichi Power Plant automatically shut down when they detected the earthquake. Damage to the power grid prompted the back-up

deiseal generators to stars automatically. These generators provided power to pumps that cool the reactor cores. Shortly

after, a 46 foot-high tsunami swept over the power plants seawall and ultimately flooded the back-up generators and cutting power

to the cooling pumps. The result was the meltdown of three reactors. Although, the Fukushima Daiichi disaster was not

as bad as the Chernobyl meltdown, it could have been much worse if sea water was not readily available to flood cool the cores and

spent fuel. However, using sea water can further damage the system over time. The Fukushima Daiichi Power Plant still faces

challenges today that can lead to more releases of radioactive contamination.

It's important to point out that both power plant disasters involved a loss of power to the cooling pumps. A nuclear power plant

cannot simply shut down and become inactive. The reactors continue to create heat and must be cooled along with spent fuel rods.

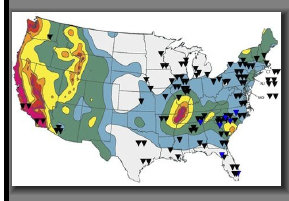

In the event of an EMP, earthquake or other disaster that damages the ability to cool the reactors and/or spent fuel, a release of

radioactive contamination will inevitably occur. If the disaster is widespread enough, several power plants could simultaneously

meltdown. Depending on current weather patterns, the contamination from each plant could spread for hundreds of miles.

In

the United States, over 100 nuclear reactors supply about 20% of our electricity. Worldwide, over 400 reactors produce 17% of

the world’s electricity. Nuclear power plants are built to strict specifications with concern for public safety. However,

with the increased threat of terrorism along with other factors such as the age of some of the facilities, the likelihood of an emergency

is increasing. In the event of an emergency (a release of radiation into the atmosphere) you should be prepared.

1. If you live within 10 miles of a nuclear power plant, you should receive materials annually regarding the unlikely event of a nuclear

power plant emergency. Review these materials thoroughly and keep them with your emergency plan.

2. If

you live within 10 miles of a nuclear power plant, learn the emergency warning systems for the power plant. If you do not know how

the power plant has planned to alert your community, contact the utility company that operates the power plant. The utility company

is required by law to have plans in place for contacting people in the community during an emergency.

3. For

those that live within 10 miles of a nuclear power plant, there is a prompt Alert and Notification System (ANS) in place to notify

the public of a power plant emergency. This system typically uses sirens, tone-alert radios, rout alerting or a combination

of these methods. If you receive or hear of an alert, tune your radio or television to a local Emergency Alert System (EAS)

station for instructions.

4. If instructed to do so by local emergency management directors and/or your

elected officials, take the potassium iodide (KI) tablets that are in your medical supplies. If you live within 10 miles of

a nuclear power plant, you may have been issued these tablets. If not, you must acquire them on your own. These tablets

can prevent radioactive iodine from concentrating in your thyroid. They do not provide protection from direct exposure to radiation

or other airborne radioactivity. Do not take them unless instructed to do so and do not take them if you are allergic to iodine.

5. Prepare an evacuation route, in advance. Make sure that your evacuation location is at least 10 miles from the power plant,

20 miles is better. Be sure that all members of your group are familiar with the route and meeting places in the event that

you become separated. During a nuclear emergency, you should listen to your TV or radio to determine if your route is the safest.

Local police officers, emergency coordinators, or government officials will alert you with radio and television messages if you need

to evacuate. Each situation can be different, and local authorities will need to find out which direction the radioactive plume is

moving before ordering people to evacuate.

6. If you are told to evacuate, do so immediately.

7. While driving, keep all of the windows and exterior vents closed. When you arrive at your destination remove your cloths and

place them in a large plastic bag. Shower thoroughly and put on fresh cloths that have not been contaminated.

8. If you have children in school, be aware of the school’s emergency plan.

You may be told not to evacuate:

Some people may be safer staying in place than they would be evacuating. For example, your child in school may be miles away from the incident, and the wind may carry the radioactive plume away from the school. It may be safer for your child to remain at school than to come home to an area where there is a danger of exposure to the radioactive plume.

Preparing a “shelter-in-place” room:

Select a room in your home that you will use to “shelter in place” if necessary. This

room should be on an upper floor, if possible, to help protect you from gases that may settle closer to the ground for chemical emergencies

but if you are more likely to be exposed to radiation, it should be on a ground floor to add additional protection from radiation.

Preferably, this room should have an attached bathroom. You should store a few important items in this room:

· First aid kit

· Flashlight, battery operated radio and extra batteries for both

· A working telephone

· Bottled water and some ready-to-eat foods that do not require

refrigeration. Do not drink water from the tap during a hazardous materials emergency. Store at least one gallon of water

per person in this room.

· Duct tape and scissors

· Towels and plastic sheeting. It is a good idea to cut your plastic sheeting to size before an emergency. You will use

it to seal all doors, windows and vents.

· Extra clothing.

· Pet supplies.

If you are told to take shelter:

1. Go indoors and stay there. Leave contaminated clothing outside.

2. Listen to your local Emergency Alert System radio or television station for emergency information. Close all doors, windows,

and vents. Turn off all fans, air conditioners, and any other source of outside air.

3. You might need to warn

a friend or family member. If so, limit time spent outdoors. While outdoors, cover your mouth and nose with a damp cloth

or towel. When returning indoors, leave outer clothing outside. Wash your face and hands with mild soap and lukewarm water.

4. Children in affected schools will be sheltered there, if necessary. Parents should not try to pick-up

school children unless advised to do so.

5. Do not pick produce or fruit. Food, produce, and packaged

food already in your home are safe to eat.

6. If you have a prepared “shelter-in-place” room, go there and

refer to your nuclear power plant emergency checklist for instructions.